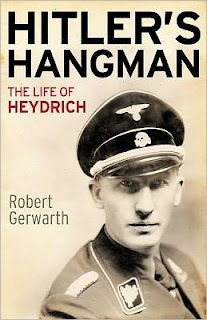

“Hitler’s

Hangman: The Life of Heydrich” by Robert Gerwarth,

Yale UP,

£20.00, 336pp,

It is peculiar that Reinhard

Heydrich has not been the subject of a few more serious-minded

biographies. After all, as the architect

of the SS-state and the master-planner of the Holocaust, he offers a unique

perspective on the inner workings of the Third Reich, whilst as an individual

he displays the sort of nefarious, Mephistophelean character traits that would

have many historians salivating.

Yet,

despite his high profile in the historical record, Reinhard Heydrich has until

now only rarely attracted the attentions of serious English-language

biographers. Robert Gerwarth’s book is

something of a rarity therefore.

It

is certainly worth the wait. Gerwarth ably

tracks the stages of Heydrich’s life; from his early years in Halle

Once installed in Himmler’s security apparatus, from

1931, Heydrich would be the driving force in the emergence of the SS,

constantly expanding its remit and espousing a perpetual radicalisation of

Nazism. He was ever vigilant, seeking

out new enemies – real or imagined – to be confronted and destroyed. Not so much a safe pair of hands, rather a

radical and utterly uncompromising administrator, Heydrich quickly emerged as

the coming man of Nazi Germany.

His

career was correspondingly stellar.

Already Himmler’s deputy, he headed the Reich Security Main Office

(RSHA) from 1939, thereby uniting all branches of the Nazi police and security

network under his control. Later, in

1941, he was appointed to head the politically sensitive and economically vital

‘Protectorate’ of Bohemia and Moravia

Gerwarth

tells this complex tale with considerable aplomb. He writes with real verve, pacing his account

well and providing the perfect mix of narrative and analysis. Pleasingly, he is not shy of indulging in a

few dramatic flourishes when the material and the circumstances allow, making

this a history book that one can genuinely read almost in a single

sitting. Moreover, he is surefooted and

admirably clear on the historical framework, not least in explaining the murky

and complex inter-relationships within the Nazi police state, and delineating

the twisted course of the genocide against the Jews.

The

Heydrich that emerges from this account is a more rounded individual from the

earlier, sometimes rather breathless, biographies. He is revealed here as a human being; a

single-minded, paranoid, psychopathic human being, but a human being

nonetheless. Interestingly – in a state

that prized physical and racial perfection – Heydrich was the only one of the

senior personnel who came anywhere close to matching the taxing ideals, despite

a persistent rumour of his part-Jewish blood.

Tall, blond, aquiline, he was an accomplished sportsman (he fenced at

national level), a gifted violinist and a trained pilot. A man of deeds rather than theories, he was

an ascetic and workaholic and he played the Byzantine world of Third Reich

politics like a chess grandmaster. He

was as close to a “Nazi Renaissance man” as it was possible to get.

Robert

Gerwarth set out to remedy the lack of a scholarly biography of Reinhard

Heydrich – one of the most pivotal and influential figures in the history of

the Third Reich. He has succeeded

admirably, producing a work that is as authoritative as it is enjoyable, and in

the process setting a new standard by which subsequent biographies of Hitler’s

‘Blond Beast’ will surely be measured.

Link to Gerwarth's "Hitler's Hangman"

This review first appeared in "History Today" in July 2012